7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.

21 September 2013 – 12 January 2014

7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.

September 21, 2013 – January 12, 2014

Opening Celebration

Friday, September 20, 2013 at 7:30 pm | Free Admission | Cash Bar

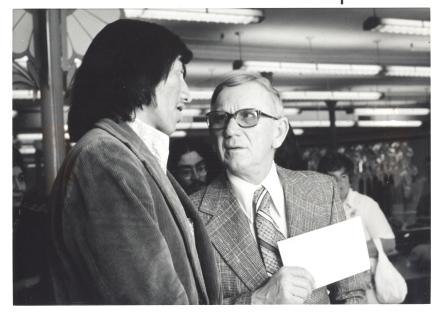

Special guests artists Alex Janvier and Joseph Sanchez, along with the exhibition curator Michelle LaVallee, were in attendance for the event.

19-year-old Jackson Beardy III, grandson of the late Jackson Beardy, performed a hoop dance and drum performance.

———————————————————————————————

A Conversation with Alex Janvier and Joseph Sanchez

Saturday, September 21, 2013 at 2:00 pm | Free Admission

A discussion with artists Alex Janvier and Joseph Sanchez, along with the exhibition curator, Michelle LaVallee.

———————————————————————————————-

7 offers diverse audiences from the many nations across Canada an unparalleled opportunity to appreciate and engage with the work by one of Canada’s most important early artist alliances—the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporated (PNIAI).

This Group of Seven was a ground-breaking cultural and political entity that self-organized to demand recognition as professional, contemporary artists, to challenge old constructs, and to stimulate a new way of thinking about contemporary First Nations people, their lives and art. Gathering informally at first in the early 1970s, Jackson Beardy (1944-1984), Eddy Cobiness (1933-1996), Alex Janvier (b. 1935), Norval Morrisseau (1932-2007), Daphne Odjig (b. 1919), Carl Ray (1942-1978) and Joseph Sanchez (b. 1948) formed this influential and historical group.

Drawing on both private and public collections the exhibition brings together 120 works including those featured in formative exhibitions of the Group along with a number of recently uncovered masterworks of the period that have not been publicly accessible for quite some time. Significant works by each member are showcased demonstrating their distinctive styles and experimentations. The selection serves to challenge the myth that PNIAI members participated in a unified “Woodland style,” as well, to substantiate the avant-gardism of the Group. The exhibition seeks to honour their efforts and recognize the contributions of these seven artists to the history of First Nations aesthetic production and to the history of art on Turtle Island.

Narratives collected from members of the group and their contemporaries will further inform the exhibition through didactic materials, catalogue text and audiovisual materials. While the exhibit both records and celebrates this history, the exhibition will also investigate this rich legacy and demonstrate how their impact continues to resonate in relation to Indigenous and Non-Indigenous contemporary art practices.

Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.

The seven artists of the PNIAI came together in order to collectively fight for the inclusion of their work within the Canadian mainstream and the contemporary art canon. Situated within a contentious political context, including the Liberal government’s controversial Indian policy of 1969, the PNIAI were resistant to colonial discourses and broke with identity definitions and boundaries imposed on First Nations. Disenchanted with the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development’s marketing and promotion strategies, they fought against exclusionary practices which treated their work as a type of handicraft, a categorization which prevented it from being shown in mainstream galleries and museums. These artists were among the first to fight to establish a long-overdue forum for the voices and perspectives of Indigenous artists: In many ways, the forward thinking of these pivotal artists led to the development and acceptance of an Indigenous art discourse and the recognition of Indigenous artists as a vital part of Canada’s past, present and future identity. By fearlessly portraying the reality of Canada from a First Nations perspective, they expanded the vocabulary of contemporary visual art practice and set a new standard for the artists who followed in their wake. Reaching across cultural boundaries, their lasting artistic merit continues to be a source of inspiration for generations to come.

Breaking Barriers

The last time there was a ceremony in our band was when I was about six years old. It was a berry festival that was being held in a birch bark lodge. The whole village was there and the priest came and told us to stop the berry festival. The priest understands now, but it is too late. The ceremony is gone. – Carl Ray

While the Group developed primarily in response to the lack of opportunities for contemporary Indigenous artists, an awareness of the pervasive attitudes and oppressive regimes that controlled the lives of First Nation individuals is key to understanding the barriers they faced. PNIAI members experienced many of the cultural and political policies that conditioned the daily experience of First Nations people, relegating them to secondary status. At the same time, there was an unyielding desire among Indigenous people to have their voices heard and to ensure a continuation of their cultural practices. The repressive social, political, and cultural contexts in Canada at the time provoked a strong resistance among artists and activists alike. The impact of the growing social and cultural movement is evident in the work of the PNIAI.

It has become my deep, personal life goal to create an awareness of our culture within the public at large – thereby cementing stronger ties of mutual understanding for one country, one Canada. – Jackson Beardy

Though their personal aspirations were diverse, as frontrunners in the early developments of contemporary First Nations art history, the collective vision of the PNIAI made contemporary Indigenous art possible. Constantly belittled, Indigenous people were faced with two options-to accept an inferior position, or rebel against oppressive conditions. Self-determination and self-definition were at the heart of PNIAI motivations. Their works provide a window upon this vision, encouraging us to think about the forces that shape our lives and how we want to shape our future together.

Creation of the Group of Seven

We had no one to show our work so we had to do it ourselves. We acknowledged and supported each other as artists when the world of fine art refused us entry…Together we broke down barriers that would have been so much more difficult faced alone. – Daphne Odjig

In 1971, Daphne Odjig and her husband Chester Beavon opened a small craft store, Odjig Indian Prints of Canada Ltd. located at 331 Donald Street in Winnipeg, Manitoba. As a gathering place, the store brought together artists who had previously worked in isolation from each other as well as the Indigenous art scenes in Ottawa and Toronto. “Odjig’s” as it was commonly referred to, offered a friendly place for artists to receive support and to discuss their challenges and aspirations. The store was a success and was expanded in 1974, establishing the New Warehouse Gallery.

By 1972, a group of artists had formed and began to call themselves the “Group of Seven.” They usually met at the North Star Inn or at Odjig’s where they shared their frustrations with the Canadian art establishment, grappled with prejudice, discussed aesthetics, and critiqued one another’s art. In November 1973, these seven artists developed a proposal to formalize their organization into the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporated (PNIAI). An application was submitted on March 14, 1974. The Group was legally incorporated on April 1, 1975 under the name Anisinabe Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., though they continued to exhibit under the moniker PNIAI.

The struggle for mainstream acceptance seemed a constant battle which pitted the artists against government programs, a non-Native public’s expectations, and government supported institutions that wanted art that reflected “Indianness” in style and content. More often than not, their work was relegated to commercial and ethno-centric galleries, cultural centres and museums, and hallways and offices, rather than contemporary fine art galleries where they felt they belonged. Members of the Group wanted to create space for contemporary artists of Native ancestry to receive support. Odjig’s provided opportunities to exhibit work and became the place to engage with other artists.

In addition to providing support to one another in their artistic endeavours, the Group’s early aims included a plan to develop a scholarship program to assist emerging artists. The PNIAI were also concerned with exclusionary practices in the art world, copyright issues, marketing strategies, and control over production of their work. Members were interested in expanding their horizons as artists rather than succumbing to a pre-packaged narrow definition of “Indian” art and double standards around authenticity.

Interacting with others who shared similar experiences and culture was both stimulating and advantageous for the PNIAI members. The camaraderie and friendship that developed helped them to navigate territory that had been difficult to traverse on their own. Whereas one voice had limits to what it could say, several artists’ voices combined created a richly diverse and powerful statement. Working together gave them a strength and unity that caught the attention of media and brought a contemporary image of First Nations art to the forefront.

“A New Language Art”

The seven artists of the PNIAI frequently drew on the legacy of their ancestors for inspiration. In doing so, they visually translated a world of knowledge based on oral tradition, individual experience, and cultural heritage. While the intention behind the artworks varies from artist to artist, each member developed their iconography to build upon this cultural inheritance. As artist Colleen Cutschall has observed, “each generation of artists adjusts to the information that precedes it, brings new ideas into discussion, and responds to the current political milieu.”

The key objectives of the Group were based on a shared concern with Indigenous philosophies, worldviews, and aesthetics. While interpretations were individually subjective and sometimes nation specific, the work produced by these seven artists was unquestionably non-European. To borrow a phrase from Robert Houle, the work was part of a “new language art,” an extension of an oral tradition via visual art. While forms, styles, and techniques varied among PNIAI members, the anatomy of this new language–their aesthetic conventions–were all truly innovative.

A commitment to nationhood and ancestry is evident throughout the PNIAI members’ oeuvres, despite the oppressive climate in which they were created. Their visual interpretations communicate a connection to a dynamic culture that is alive and well. Shirley Madill articulates it best in Jackson Beardy: A Life’s Work:

Spirits, heroes, animals and references to natural elements in various stages of transformation are not simply “stories.” They express the logic proper to a culture and its social and moral organization through images and words taken from the community’s environment and experience. These works not only demonstrate the permanence of traditional [Indigenous] culture, but also reveal the presence of living, creative sources that, firmly rooted in the multi-cultured world of today, open the way to a more understanding world tomorrow. (1993)

The subject matter explored by the PNIAI members is diverse, with content that is anecdotal, humorous, spiritual, and political. Some of the work is personal in nature and is based on biographical narratives and everyday life. Other work takes on social issues related to history, government and ecology. Still other works turn to legends and the supernatural for inspiration to articulate spiritual beliefs and to understand dualities and conflict.

The PNIAI were frontrunners in shaping First Nations aesthetic production. In recording Indigenous histories, they contributed to the revitalization of First Nations culture. The PNIAI assert and reveal the contemporary relevance of Indigenous peoples, ideologies and cultures, and continue to inspire current and future generations.

Storytelling: History and Narrative

Art is not a substitute for oral storytelling,but another means to describe and explain reality. As Alex Janvier has said, “this is my way of speaking to the public…my visual language…to convey what’s inside my spirit.”

The concept of narrative–sending messages, telling stories, documenting histories, or relating everyday experiences–permeates the exhibit. The artist is Storyteller. Adventures are recounted, conflicts described, and experiences with government and church recorded. Stories are reanimated through their work and linked to the experiences of individuals and histories of communities.

The artworks included here record moments from our shared histories for contemplation and remembrance. Few paintings portray a complete narrative, whether literal or symbolic. However, their statements always engage larger concerns with culture and humanity.

Storytelling: Supernatural Beings and the Spirit World

I paint what I believe. What is secret I don’t paint. I can’t paint anything if I don’t have the background and the cultural knowledge to make it right. It wouldn’t be fair to my people and it wouldn’t be fair to the rest of Canada. – Jackson Beardy

Indigenous cultural traditions have a long and continuous history in North America. PNIAI members sought to reconnect with these traditions through the myths and narratives of their various nations. These distinctly non-western stories instruct us how to act in the world and interact with the myriad of beings around us. The stories provide moral lessons about life in this land. The narrative legends presented here are not appropriations of the sacred, but as art historian and artist Sherry Farrell Racette affirms, “a powerful reclaiming of an ancient form of visual storytelling…created by previous generations.” (Sherry Farrell Racette, “Algonkian Pictographic Imagery,” Selected Proceedings of Witness: A Symposium on the Woodland School of Painters, 2009).

Prominent among the depictions of the PNIAI are various manitous. Author Basil Johnston explains that manitous are beings or forces fused into physical bodies or objects. These unseen beings are often beyond the earth, while others live with human beings and creatures.

The Thunderbird is a cross-cultural figure prevalent in many First Nations mythologies and narratives. “Of all the manitous who presided over the destinies and affairs of humankind, none [is] more revered for its potency and preeminence than was the thunderbird” (Basil Johnston, The Manitous: the supernatural world of the Ojibway, 1995). Thunderbirds represent the powers of the sky, producing thunder by flapping their wings and lightning by opening and closing their eyes. Johnston tells us that Thunderbird was “created to tend to Mother Earth’s health and well-being, to give her drink when she is thirsty, to cleanse her form and her garments when she needs refreshment, to keep her fertile an fruitful, and to stoke fires to regenerate the forests. From early spring to late fall, the thunderbirds were vigilant…and in winter, they rested.” Many members of the PNIAI have been inspired by the Thunderbird, but depictions vary as they reflect each artist’s interpretation of the great being and its power.

Storytelling: Personal Narrative

Perhaps the mot common kind of storytelling occurs at the kitchen table or in the living room, around a fire, on the road, or in a coffee shop. When we gather with family or friends, this personal type of storytelling enriches interactions and maintains connections. The stories can be humorous, emotional, dramatic or mundane but everyone has a story to be told, whether tales of adventure, memories from youth, or moments with close friends.

There are historical precedents for this type of narrative. In most First Nations cultures, pictographs were used not only for sacred or spiritual purposes, but also “to leave messages, tell stories, and document everyday experiences” (Racette).

Many of the works in the exhibition are personal in nature. Through storytelling, we are offered a glimpse into the experience of the seven artists of the PNIAI. Subject matter may reflect biographical narratives, reference dreams and visions, or relate everyday stories from the lives of the artists.

Spirituality & Ceremony

Spirituality and ceremony is a theme found in the works of many of the PNIAI members. Tradition, ceremonial practices and spiritual beliefs give form to Indigenous worldviews and shape the experience and perception of the world. For each artist, spirituality is a personal and communal journey. They have each embraced and engaged with the traditions of their own communities in varying ways.

Several of these images reflect the artist’s interest in keeping traditions alive and a desire to reveal the contemporary relevance of traditional ways. The artworks mirror personal experience; what we see is what the artist has chosen to share with us about their spiritual journey and their experience with various ceremonies. Other works explore connections between belief systems or consider the influence of traditions outside their own.

Duality & Conflict

Seeking balance and understanding the origins of conflict within our everyday lives is a reoccurring theme in the works of PNIAI members. This section of the exhibition features work by Daphne Odjig, Norval Morrisseau, Alex Janvier, Jackson Beardy and Joseph Sanchez that explore inner turmoil, and reflect on the personal or cultural imbalance experienced by the artists.

The conflict between good and evil is a concept common to all religions and one which reaches across cultural boundaries. This age old duality is a theme explored by Odjig, Morrisseau, Ray and Sanchez in a continued effort to understand the forces that shape the world we live in. The polarities of good and evil take shape in beings that are connected with the forces of the universe, but they are also manifest in the physical world in the lives and circumstances of individuals.

The Natural Word & Everyday

Indigenous world views include an understanding of our inherent connection to the land and other non-human beings. These works are a reminder of this relationship. Surrounded by storied landscapes, the PNIAI artists draw from their memories and experiences of land, nature, and community. Complex worlds beyond our own are revealed in individual impressions of mother earth, the elements, and the flora and fauna of a beloved territory. Richly layered with meaning and emotion, the artworks capture a perception of the world that encourages reflection on concepts of life, nature, and their inherent beauty.

7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., installation at the MacKenzie Art Gallery, 2013. Photo: Don Hall.

7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. is organized by the MacKenzie Art Gallery. This project has been made possible through a contribution from the Museums Assistance Program, Department of Canadian Heritage. The MacKenzie receives ongoing support from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, SaskCulture, the City of Regina, and the University of Regina.

7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. catalogue wins three awards at the Saskatchewan Book Awards

Regina, SK – The MacKenzie Art Gallery is pleased to announce that 7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. received three awards for publishing at the Saskatchewan Book Awards on April 25, 2015, including the University of Regina Faculty of Education and Campion College Award for Publishing in Education, the First Nations University of Canada Aboriginal Peoples’ Publishing Award, and the Ministry of Park, Culture and Sport Publishing Award. Read more…

Second Edition Available for Purchase now!

The award-winning catalogue 7: PNIAI is back in stock. Please visit the MacKenzie Gallery Shop to purchase your copy today.

Tour dates for this exhibition:

Winnipeg Art Gallery Winnipeg, MB May 9 to August 31, 2014

Kelowna Art Gallery Kelowna, BC October 11, 2014 to January 4, 2015

McMichael Canadian Art Collection Kleinburg, ON May 10 to September 7, 2015

Art Gallery of Windsor Windsor, ON October 2, 2015 – January 17, 2016

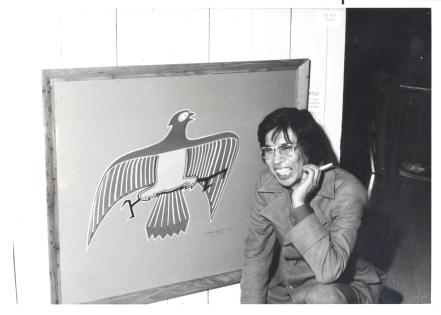

jbeardy

Jackson Beardy (1944–1984) was born on the Garden Hill Reserve (Island Lake, Manitoba) and was of Cree ancestry. Beardy studied commercial art at the Winnipeg Vocational School (1963–64) and later took art classes at the University of Manitoba. Throughout his career, Beardy served as a member of numerous arts organizations, including: National Indian Art Council, Ottawa; Prison Arts Foundation, Ottawa; Manitoba Arts Council, Winnipeg; and Canadian Artists Representation / le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC). He also served as the president of the Canadian Indian Artists Association and was founder and president of Ningik Arts (1972). He is the recipient of the Canadian Centennial Medal (1967), the Junior Achievement Award (1974), and the Outstanding Young Manitoban Award (1982).

Beardy has acted as art adviser and cultural consultant to the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature (1971), the Department of Native Studies at Brandon University (1972), and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada) (1981). While at DIAND, he authored Indian Fine Arts: A Policy and Programme to guide the programming and collecting of the department. A noted book illustrator, he was also contracted by the department to record and illustrate the “legends of the people” while travelling throughout the North. His illustrations have been published in John Morgan’s book, When the Morning Stars Sang Together (1974). Beardy also designed the cover art for two books: Leonard Peterson’s Almighty Voice (1976), and Basil Johnston’s Ojibway Heritage (1976).

Image: Jackson Beardy, 1975

National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Dominion Gallery Fonds

eddycobiness

Eddy Cobiness (1933–1996) was born in Warroad, Minnesota and raised on Buffalo Point Reserve, Manitoba. Between 1954 and 1957, Cobiness served in the United States Army, where he became a Golden Gloves boxer and continued to draw and sketch during his leisure time. In 1980, he served as chairman of the First Annual Great Peoples PowWow in Sprague, Manitoba. He has also published his illustrations in two books: Alphonse Has an Accident (1974) and Tuktoyaktuk 2-3 (1975).

An Ojibway artist, Cobiness participated in several exhibitions as a member of PNIAI throughout the 1970s, including: Canadian Indian Art ’74, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (1974); Indian Art ’75, Woodland Cultural Centre, Brantford (1975); and Colours of Pride: Paintings by Seven Professional Native Artists / Fierté sur Toile, Dominion Gallery, Montreal (1975). His works have also been included in two recent group exhibitions: Frontrunners, co-organized by Winnipeg’s Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art and Urban Shaman Contemporary Art Gallery and Artist-Run Centre, Winnipeg (2011); and My Winnipeg: There’s No Place Like Home, Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg (2012). His work is held in many prominent private collections worldwide including those of former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, Queen Elizabeth II, and former Manitoba Premier Edward Schreyer. His work is found in several public collections, including: Canadian Museum of Civilization (QC); Department of Indian and Northern Affairs (ON); McMichael Canadian Art Collection (ON); Royal Ontario Museum (ON); and Woodland Cultural Centre (ON).

Image: Eddy Cobiness, 1975

National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Dominion Gallery Fonds

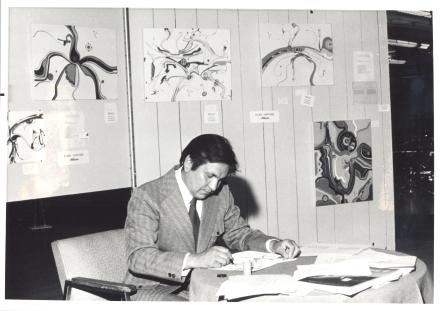

alexjanvier

Alex Janvier (b. 1935) was born at Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, and is of Dene Suline and Saulteaux heritage. In 1960, Janvier received his Fine Arts Diploma with Honours from the Alberta College of Art in Calgary, after which he worked as an art instructor at the University of Alberta (1961). Janvier was later hired as a cultural adviser to the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs (now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada) and helped to establish cultural policy for the Cultural Affairs Program (1965). He was also appointed to the Aboriginal Advisory Committee for the Indians of Canada pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, where he painted a nine-foot circular mural titled Beaver Crossing Indian Colours.

Janvier has been the recipient of several honours over the years. These honours include Lifetime Achievement awards from the Tribal Chiefs Institute, Cold Lake First Nations (2001), and the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation (2002); the Centennial Medal for outstanding service to the people and province of Alberta (2005); the Order of Canada (2007); the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts (2008); the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Marion Nicoll Visual Arts Award (2008); the Alberta Order of Excellence (2010); and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal (2013). Janvier has also received honorary doctorates from the University of Alberta (2008), the University of Calgary (2008), and Blue Quills First Nations College (2012).

Image: Alex Janvier, 1975

National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Dominion Gallery Fonds

nmorrisseau

Norval Morrisseau (1932–2007) was raised on the Sand Point Reserve near Lake Nipigon and was of Ojibwa descent. Since his first solo exhibition at the Pollock Gallery, Toronto, in 1962, Morrisseau’s career has been marked by firsts. He was the only painter from Canada invited to exhibit in the Magiciens de la Terre / Magicians of the Earth exhibition at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris (1989), and he was the first artist of First Nations descent to have a retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2006). A recipient of numerous awards and honours in his lifetime, Morrisseau received the Canadian Centennial Medal (1968), was elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Art (1973), and was inducted into the Order of Canada (1978). In 1980, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by McMaster University. He was acknowledged as Grand Shaman of the Ojibway in Thunder Bay (1986) and honoured by the Assembly of First Nations Chiefs Conference in Ottawa (1995).

Morrisseau was among the artists selected to participate in the Indians of Canada pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, Quebec, and was a founding member of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. In 1971, Norval Morrisseau and fellow PNIAI member Carl Ray toured reserves and communities of Northern Ontario as part of a federally sponsored Northern Art Tour (1971–72). He was also featured in the National Film Board of Canada’s documentary The Colours of Pride (1973) with Alex Janvier and Daphne Odjig. In 1974, a documentary titled The Paradox of Norval Morrisseau was released by the National Film Board of Canada. Morrisseau wrote and illustrated Legends of My People, The Great Ojibway (1965) and co-authored Norval Morrisseau: Travels to the House of Invention (1997).

Image: Norval Morrisseau, 1975

National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Dominion Gallery Fonds

daphneodjig

Daphne Odjig (1919 – 2016) was born on Wikwemikong (Manitoulin Island) and is of Potawatomi and Odawa heritage. Odjig was admitted to the British Columbia Federation of Artists in 1963, and in 1970 she established Odjig Indian Prints of Canada Limited in Winnipeg. She served as a member of the board and instructor for the Manitou Arts Foundation on Schreiber Island, Ontario (1971). In 1973, Odjig received a Swedish Brucebo Foundation Scholarship and travelled as a resident artist to Sweden. Odjig has been the recipient of several awards and honours, including: the Canadian Silver Jubilee Medal (1977); an Eagle Feather on behalf of the Wikwemikong Reserve in recognition of her artistic accomplishment, an honour previously reserved for men (1978); the Order of Canada (1986); the National Aboriginal Achievement Award (1998); the Commemorative Golden Jubilee Medal (2002); the Order of British Columbia (2007); and the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts (2007). She has been awarded honorary doctorates by Laurentian University, Sudbury (1982), University of Toronto (1985), Nipissing University, North Bay (1996), Okanagan University College, Kelowna (2002), Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops (2007), Ontario College of Art and Design, Toronto (2008), University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario (2008), and Algoma University, Sault Ste. Marie (2011). Odjig has been an honorary board member of the Canadian Heritage Foundation (1988–93) and is an elected member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Art (1989).

In 1971, Odjig opened a small craft store in Winnipeg. This craft store was expanded in 1974 to create the New Warehouse Gallery, the first gallery owned and operated by a person of Indigenous heritage in Canada. Two feature documentaries have been produced about Odjig’s life and work: Colours of Pride (1973) and The Life and Work of Daphne Odjig (2008). Odjig has written and illustrated a series of school readers, Nanabush Tales (1971), which are still included as part of the curriculum in elementary schools on Manitoulin Island.

Image: Daphne Odjig, 1975

National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Dominion Gallery Fonds

carlray

Carl Ray (1943–1978) was born on the Sandy Lake Reserve, Ontario, and was of Cree heritage. Ray completed commissioned work (alongside Norval Morrisseau) for the Indians of Canada pavilion at Expo 67, later receiving grants from the Canada Council (1969) and the Department of Health and Welfare, Indian Affairs Branch (1971). In 1971, Ray was an instructor at the Manitou Arts Foundation’s summer art camps at Schreiber Island (ON) and editor of the Kitiwin newspaper in Sandy Lake (ON). The Government of Ontario and the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs (now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada) sponsored the Northern Art Tour (1971–72), in which Ray and Norval Morrisseau toured through reserves and communities of Northern Ontario. Ray illustrated James Stevens’ book, Sacred Legends of the Sandy Lake Cree (1971), and also illustrated the cover of Tom Marshall’s book The White City (1976).

Ray has had solo exhibitions at Brandon University, Manitoba (1969); Confederation College, Thunder Bay (1970); Aggregation Gallery, Toronto (1972–77); Galerie Fore, Winnipeg (1972); and the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (1972). His work has also been displayed in a number of group exhibitions with other PNIAI members, including two exhibitions at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery: The Art of the Anishnabe (1993) and Water, Earth and Air (1997). Other group exhibitions include: Canadian Indian Art ’74, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (1974); Indian Art ’75, Woodland Indian Cultural Education Centre, Brantford (1975); Colours of Pride: Paintings by Seven Professional Native Artists / Fierté sur Toile, Dominion Gallery, Montreal (1975); Contemporary Native Art of Canada — The Woodland Indians, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (1976); Contemporary Indian Art — The Trail from the Past to the Future, Trent University, Peterborough (1977); and Contemporary Indian Art at Rideau Hall, Department of Indian and North Affairs, Ottawa (1983). His work is held in numerous public and private collections, including: Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (ON); Art Gallery of Ontario (ON); Canadian Museum of Civilization (QC); McMichael Canadian Art Collection (ON); National Gallery of Canada (ON); Government of Ontario Art Collection (ON); and Winnipeg Art Gallery (MB). Major commissions include murals for the Sandy Lake Primary School, Ontario (1971) and the Sioux Lookout Fellowship and Communication Centre, Ontario (1973).

Image: Carl Ray, 1975

National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Dominion Gallery Fonds

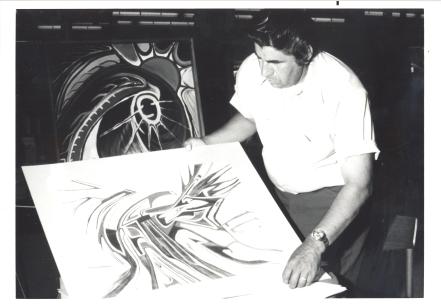

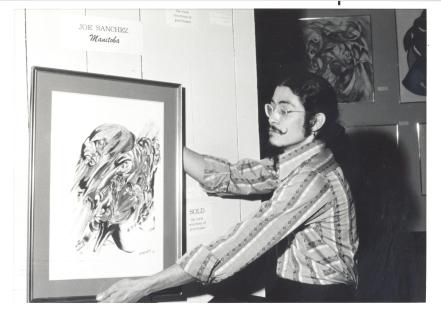

josephsanchez

Joseph Sanchez (b. 1948) was born in Trinidad, Colorado. He is an artist and curator of Spanish, German, and Pueblo descent currently residing in Santa Fe, New Mexico. From 1982–84 he served as a board member of the National Association of Artist Organizations. In 2010, Sanchez retired as Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (formerly the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum), where he had worked since 2002. In 2011, Sanchez was the Contemporary Curator of the exhibition Native American Art at Dartmouth: Highlights from the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth University, Hanover, New Hampshire. Sanchez was the recipient of the Allan Houser Memorial Award for outstanding artistic achievement and community service in 2006 and was a curatorial partner for the 7th International Biennial at Site Santa Fe in 2008.

The only non-Canadian artist of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., Sanchez served in the United States Marine Corps before moving to Canada. He met Daphne Odjig in 1971 while living outside of Winnipeg in Richer, Manitoba, and was instrumental in the formation of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. In 1975, Sanchez was repatriated under the Gerald Ford Presidential Amnesty and moved to Arizona, where he was involved with the formation of the artist groups MARS (Movimiento Artistico del Rio Salado) and Ariztlan in 1978. In 1983 Sanchez founded ARTS, a service to design exhibitions, provide curatorial services, administer collections, and provide consulting for individuals, artists, and museums.

Image: Joseph Sanchez, 1975

National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Dominion Gallery Fonds

Events

-

![Three figures march through the winter snow carrying a transparent canoe shaped structure that glows from the inside.]()

Studio Sunday

It’s 2050: Sci-fi comics

28 April 2024

-

![A wax figure of a lady in all black with four arms, each arm is controlling a small puppet.]()

Studio Sunday

Artist Workshop with Sylvia Ziemann

5 May 2024

-

![Still from Wednesday Kim's Sleep Deprived Workers (detail), 2019--2020. Courtesy of the artist.]()

Online Event

Wake Windows: The Witching Hour Virtual Opening

9 May 2024